Some Final Thoughts

In the past nine weeks, I have tried to explore different

contemporary manifestations of the original Net Art movement. At times, it was surprisingly

difficult to find specific examples of artistic creations that matched my

definition of Net Art: “instances of artistic expression that rely on the

Internet for existence”. Often times, I would find something interesting, but

it would not match my definition. I believe that this difficulty was due in

part to the fact that, as I said in my second post, “net art…is still in its

fledgling stages”. Indeed, in my time spent researching for this blog, I never

once came across the phrase “net art” or even a vague reference to the original

movement.

In light of this lack of popularity, it may be tempting to

label the short-lived Net Art movement as unimportant or irrelevant. However, I

would disagree wholeheartedly. The movement took a very cutting-edge artistic

approach to creating art with the Internet that is still relevant to today. The

ideas that these early pioneers explored are being re-discovered by

contemporary Net-Artists. For example, in my last blog post, I wrote about an

interactive music video called “The Wilderness Downtown”. This application uses

Google-maps information to construct a personalized viewing experience for

every user. This idea of interactive narratives was present very early on in

Net Art’s history. In a net art piece from 1996 by Olia Lialina called “My Boyfriend Came Back From the War”, viewers explore a sort of virtual pop-up

book by clicking links and images in their browser. Each click reveals a little

fragment about the artist’s relationship with her recently returned veteran

boyfriend. To be honest, it is a very cryptic narrative that doesn’t compare to

the raw graphical complexity of “The Wilderness Downtown”. Still, however, with

such limited tools, this artist was able to create a very distinct atmosphere

within the piece. The fractured dialogue and stark visual landscape conveys the

apparent sense of emotional disconnect between the artist and her veteran

boyfriend. Likewise, “The Wilderness Downtown” uses Google maps and animation

to communicate the themes of nostalgia and perdition in the Arcade Fire song

“We Used to Wait”. Despite being created at very different times during the

Internet’s evolution, both pieces utilize the Internet’s ability to involve the

viewer in the artwork. At heart, they are both interactive narratives. They

only differ in the technological capacity for visual and sensory impact.

In short, Net Art is still alive and relevant. But, what impact

will it have on the world?

I believe Net Art’s greatest potential contribution to the

world is to demystify part of the creative process. The average person tends to

view individual artworks in isolation. In this paradigm, artworks are seen as

representations of ideas that were created in a vacuum or some esoteric, unapproachable

place. Essentially, they lack context. For example, many people view Picasso as

a totally unique artistic phenomenon. Although he was definitely a masterful

artist, his ideas and even his artistic style did not just magically come into

existence. His artwork was heavily influenced by the work of African mask

makers and contemporaries, like Braque and Cezanne.

For example, which of these pieces is by Braque and which is by Picasso?

Nothing, even the most spectacular, is created from nothing. Yet, for the average person looking at a single Picasso

painting in a gallery filled with hundreds if not thousands of other artistic

works, it can be very difficult to see these connections; to see history of

creative thoughts that finally were synthesized and displayed on a single linen

canvas. The evolution of ideas is not immediately evident, nor is it readily

available to viewers standing in front of the canvas. To learn more, one has to

have suitable motivation to take the time to search through different sources:

books on art history or various websites.

I feel that Net Art has the ability to present this

evolution of ideas in the same space as the actual artwork. Chromeexperiments.com is a prime example of this. Viewers can explore individual creative projects

that present innovative uses of WebGL, CSS3 and HTML5 and sometimes examine the

actual code. However, these individual artworks are presented along side a

whole collection of other works that use the same tools and riff off each

other’s ideas. Or, to go a step further, Net Art can actually make the process

a tangible part of the artwork. This type of thinking is perfectly encapsulated

by the Koblin piece “The Exquisite Forest”. The whole point of this work is to

examine the way people creatively expand on each other’s ideas. Similarly, his

other works “The Johnny Cash Project” and “The Sheep Market” allow viewers to

look at the creation of individual components of the overall piece. In both

these examples, the creative process – the evolution of ideas – makes up a

large portion of the actual artwork.

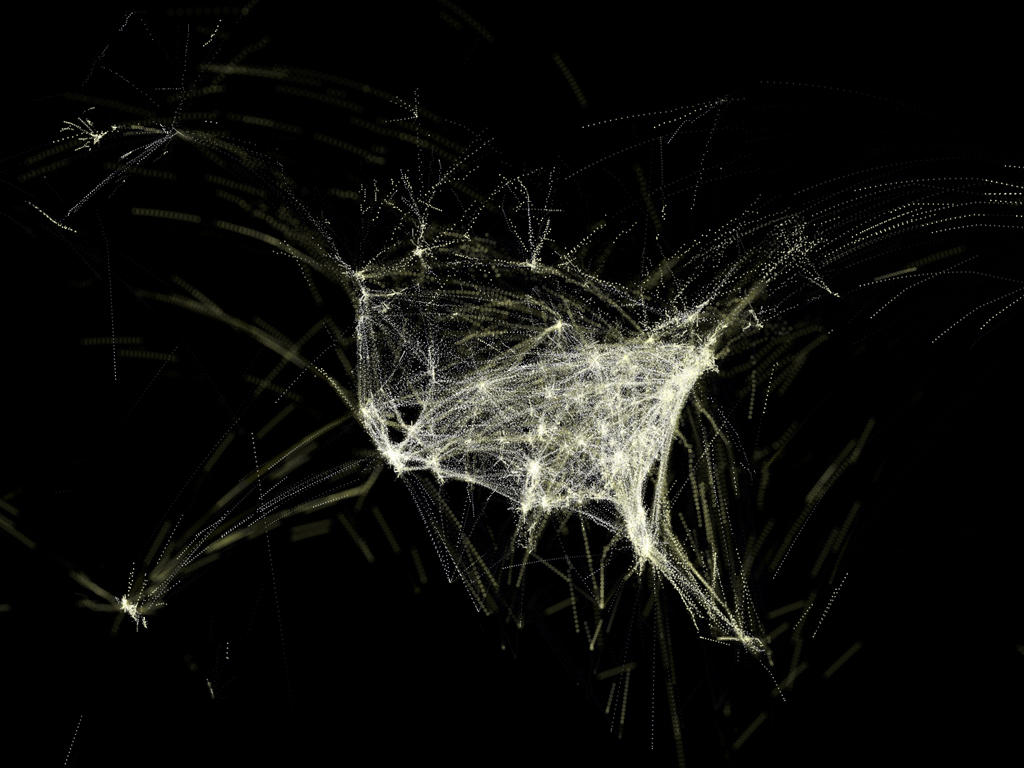

All of this contributes to the idea that the Internet is the

manifestation of human kind’s collective mind. The conscious results of unconscious

creative processes can now all be found in one place – the Internet. The

context and consequences of a single idea are now easily accessible and

contained within a single system. Instead of seeing a painting in one place and

learning about its history in another, all of this will be done through a

single system or medium - the Web.

As all the people and computers on our planet get more and more

closely connected, it's becoming increasingly useful to think of all the people

and computers on the planet as a kind of global brain.

- THOMAS W. MALONE, Patrick J. McGovern Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management and founding director of the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence.